In order to reproduce, birds must find a suitable mate,

or mates, as well as the necessary resources-food, water,

and nesting materials-for caring for their eggs and

raising the hatched young to independence. Most birds

mate during a specific season in a particular habitat,

although some birds may reproduce in varied places and

seasons, provided environmental conditions are suitable.

Most birds have monogamous mating patterns,

meaning that one male and one female mate exclusively

with each other for at least one season. However, some

bird species are either polygynous, that is, the males

mate with more than one female, or polyandrous, in which

case the females mate with more than one male (see Animal

Courtship and Mating). Among many types of birds, including

some jays, several adults, rather than a single breeding

pair, often help to raise the young within an individual

nest.

|

Birds rely heavily on their two

main senses, vision and hearing, in courtship

and breeding. Among most songbirds, including

the nightingale and the sky lark, males use song

to establish breeding territories and attract

mates. In many species, female songbirds may be

attracted to males that sing the loudest, longest,

or most varied songs. Many birds, including starlings,

mimic the sounds of other birds. This may help

males to achieve sufficiently varied songs to

attract females.

Numerous birds rely on visual

displays of their feathers to obtain a mating

partner. For example, the blue bird of paradise

hangs upside down from a tree branch to show off

the dazzling feathers of its body and tail. A

remarkable courtship strategy is exhibited by

male bowerbirds of Australia and New Guinea. These

birds attract females by building bowers for shelter,

which they decorate with colorful objects such

as flower petals, feathers, fruit, and even human-made

items such as ribbons and tinfoil.

|

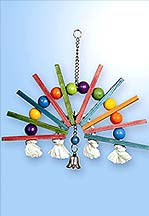

very

large bird cages

very

large bird cages

|

Among some grouse, cotingas, the small wading

birds called shorebirds, hummingbirds, and other groups,

males gather in areas called leks to attract mates through

vocal and visual displays. Females visiting the leks

select particularly impressive males, and often only

one or a very few males actually mate. Among western

grebes, both males and females participate in a dramatic

courtship ritual called rushing, in which mating partners

lift their upper bodies far above the water and paddle

rapidly to race side by side over the water's surface.

Although male birds usually court females, there are

some types of birds, including the phalaropes, in which

females court males.

Many birds establish breeding territories, which they

defend from rivals of the same species. In areas where

suitable nesting habitat is limited, birds may nest

in large colonies. An example is the crab plover, which

sometimes congregates by the thoUKnds in areas of only

about 0.6 hectares (about 1.5 acres).

For breeding, most birds build nests,

which help them to incubate, or warm, the developing

eggs. Nests sometimes offer camouflage from predators

and physical protection from the elements. Nests may

be elaborate constructions or a mere scrape on the ground.

Some birds, including many shorebirds, incubate their

eggs without any type of nest at all. The male emperor

penguin of icy Antarctica incubates the single egg on

top of its feet under a fold of skin.

Bird nests range in size from the tiny

cups of hummingbirds to the huge stick nests of eagles,

which may weigh a ton or more. Some birds, such as the

malleefowl of southern Australia, use external heat

sources, such as decaying plant material, to incubate

their eggs. Many birds, including woodpeckers, use tree

cavities for nests. Others, such as cowbirds and cuckoos,

are brood parasites; they neither build nests nor care

for their young. Instead, females of these species lay

their eggs in the nests of birds of other species, so

that the eggs are incubated-and the hatchlings raised-by

birds other than the hatchlings' true parents.

Incubation by one or both parents works

together with the nest structure to provide an ideal

environment for the eggs. The attending parent may warm

the eggs with a part of its belly called the brood patch.

Bird parents may also wet or shade the eggs to prevent

them from overheating.

The size, shape, color, and texture

of a bird egg is specific to each species. Eggs provide

an ideal environment for the developing embryo. The

shells of eggs are made from calcium carbonate. They

contain thoUKnds of pores through which water can evaporate

and air can seep in, enabling the developing embryo

to breathe. The number of eggs in a clutch (the egg

or eggs laid by a female bird in one nesting effort)

may be 15 or more for some birds, including pheasants.

In contrast, some large birds, such as condors and albatross,

may lay only a single egg every two years. The eggs

of many songbirds hatch after developing for as few

as ten days, whereas those of albatross and kiwis may

require 80 days or more.

Among some birds, including songbirds

and pelicans, newly hatched young are without feathers,

blind, and incapable of regulating their body temperature.

Many other birds, such as ducks, are born covered with

down and can feed themselves within hours after hatching.

Depending on the species, young birds may remain in

the nest for as little as part of a day or as long as

several months. Fledged young (those that have left

the nest) may still rely on parental care for many days

or weeks. Only about 10 percent of birds survive their

first year of life; the rest die from starvation, disease,

predators, or inexperience with the behaviors necessary

for survival. The age at which birds begin to breed

varies from less than a year in many songbirds and some

quail to ten years or more in some albatross. The life

spans of birds in the wild are poorly known. Many small

songbirds live only three to five years, whereas some

albatross are known to have survived more than 60 years

in the wild.

|